Notes on nodejs

- Notes on nodejs

- Required Javascript

- Node

- The Node REPL (read-eval-print loop)

- Running a Program with Node

- Core Modules

- Console Module

- The Process Module

- The OS Module

- The Util Module

- NPM

- Create a new app

- nodemon

- Package Scope

- Installing a Custom Package

- Modules

- Exporting

- Require

- Using Object Destructuring to be more Selective With require()

- The Events Module

- User Input and Output

- The Error Module

- Why Error First Callbacks

- The Buffer Module

- Readable Streams

- Further explanation

- Writable Streams

- Timers Modules

- HTTP Server

- The URL Module

- Routing

- Longer Example

- Returning a Status Code

- Express

- Knex.js

- Babel

- ReactJS

- Importing React Required Code

- Components

- Create a Component Class

- The Render Function

- Create a Component Instance

- Use This in a Class

- Render Components with Components

- Importing Files and Exporting Functionality

- Component Props

- Event Handler

- handleEvent, onEvent, and this.props.onEvent

- this.props.children

- Default Properties

- Component State

- Component Lifecycle

- componentDidMount

- componentWillUnmount

- componentDidUpdate

- Stateless Functional Components

- Function Component Props

- React Hooks

- Update Function Component State

- Initialize State

- Use State Setter Outside of JSX

- Set From Previous State

- Arrays in State

- Objects in State

- Separate Hooks for Separate States

- The Effect Hook - useEffect

- React Hooks and Component Lifecycle Equivalent

- Function Component Effects

- Clean Up Effects

- Control When Effects are Called

- Fetch Data from a Server

- Rules of Hooks

- Separate Hooks for Separate Effects

- Stateless Components from Stateful Components

- Build a Stateful Component Class

- Don't Update props

- Child Components Update Their Parents' State

- Child Components Update Sibling Components

- One Sibling to Display, Another to Change

- Style

- Inline Styles

- Make a Style Object Variable

- Share Styles Across Multiple Components

- Separate Container Components from Presentational Components

- Create a Container Component

- Create a Presentational Component

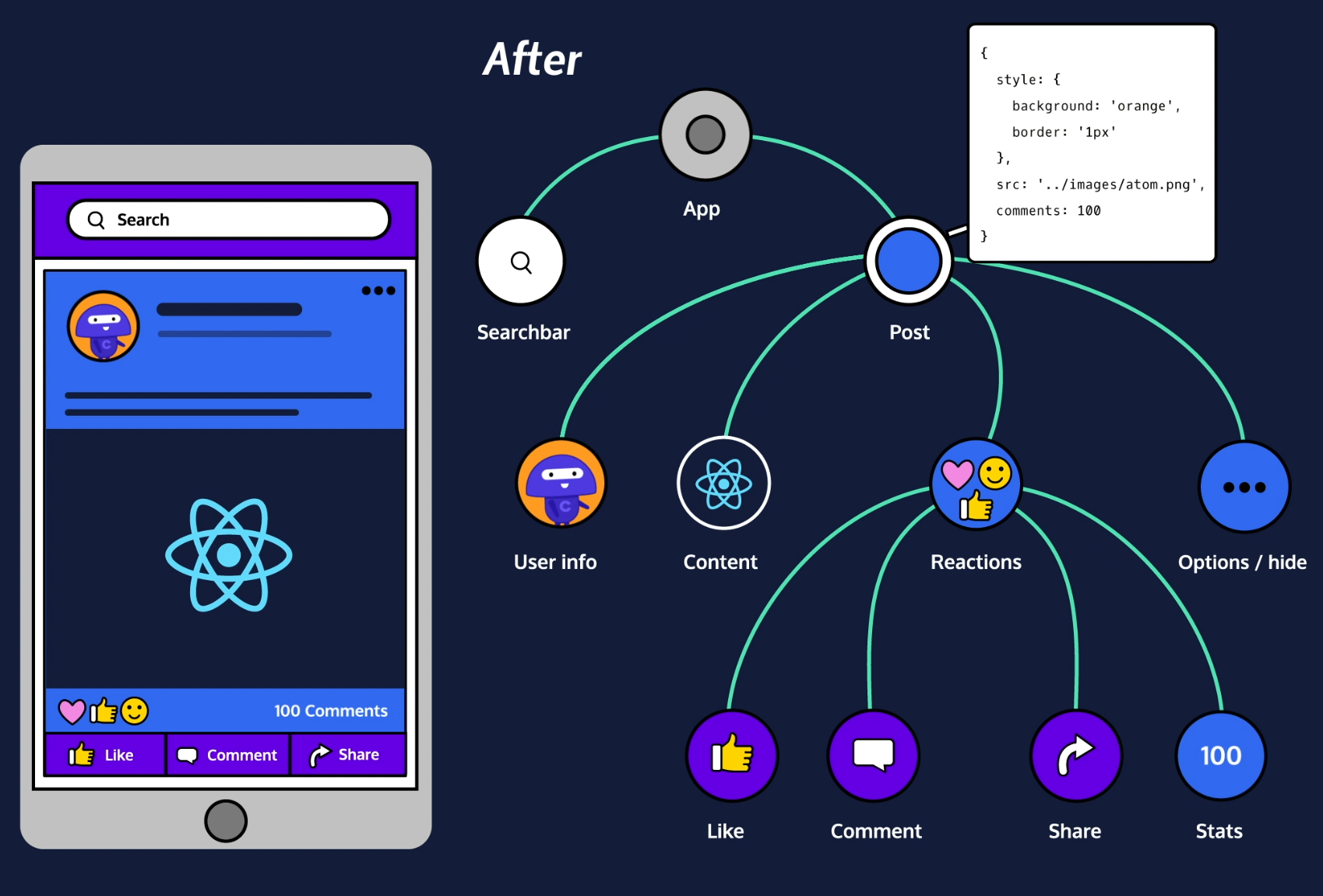

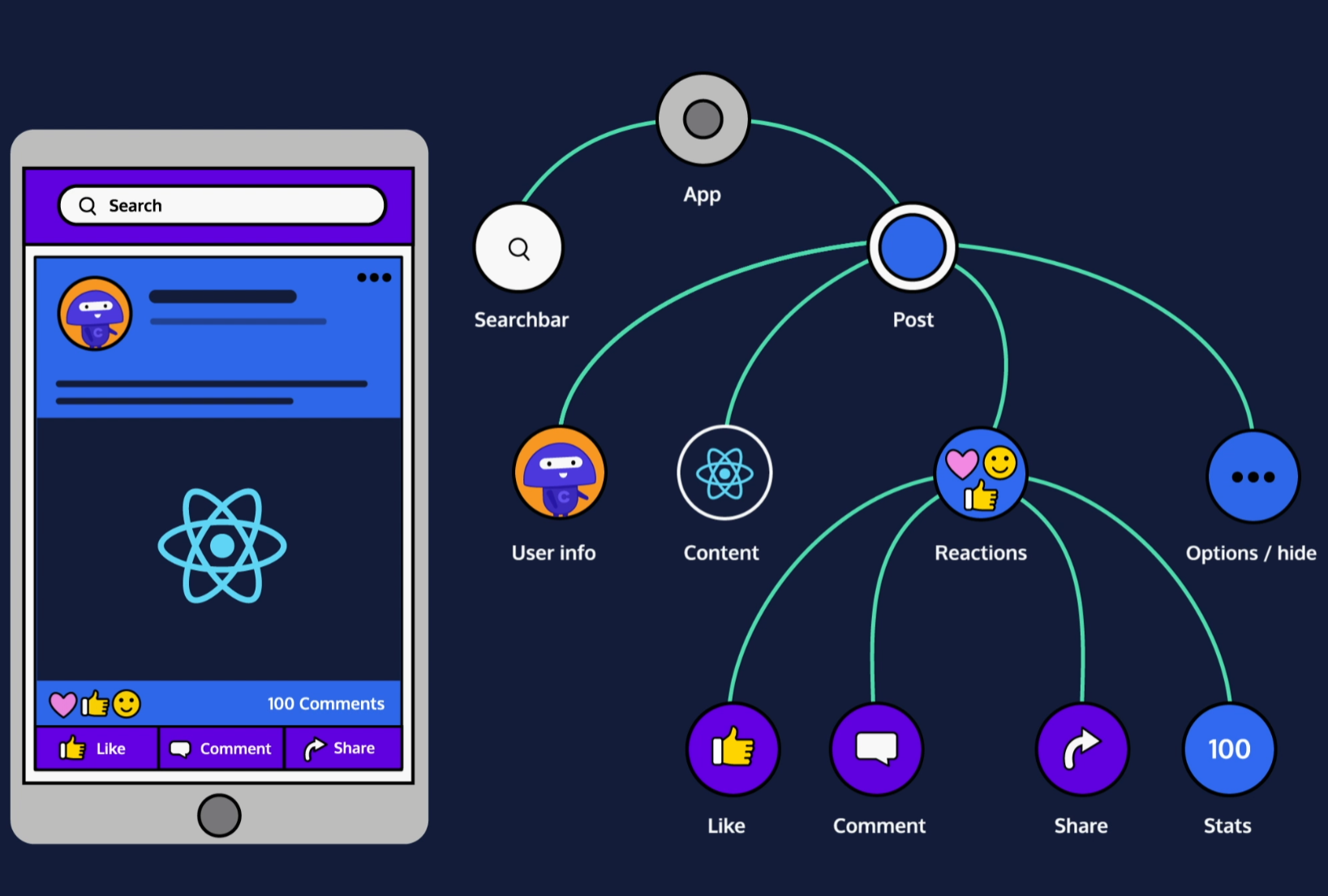

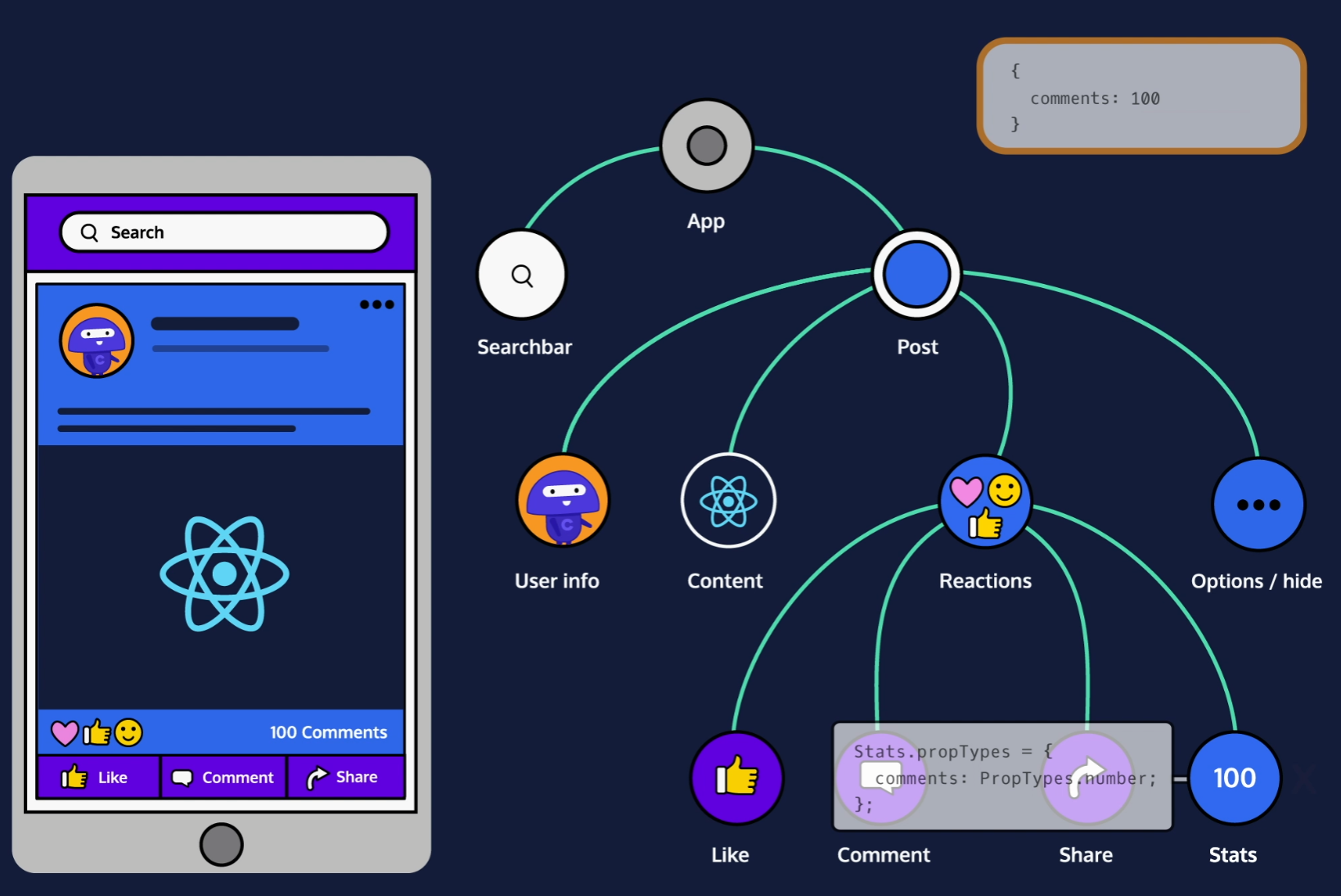

- propTypes

- Apply PropTypes

- PropTypes in Function Components

- React Forms

- Input on Change

- Control vs Uncontrolled

- Update an Input's Value

- Set the Input's Initial State

- Dynamically Rendering Different Components without Switch: the Capitalized Reference Technique

- React Router

- BrowserRouter

- Route

- Routes

- Links

- URL Parameters

- Nested Routes

- Pass props to Router Components

- Good Practices for Calling APIs from ReactJS

- JSX

- JSX Elements

- JSX Elements And Their Surroundings

- Attributes In JSX

- Nested JSX

- JSX Outer Elements

- Rendering JSX

- ReactDOM.render()

- class vs className

- Self-Closing Tags

- Javascript in JSX

- Variables in JSX

- Event Listeners in JSX

- JSX Conditionals

- .map in JSX

- List Keys

- React Create Element

Required Javascript

Arrow expressions

Let’s take a look at the code below. You will see two different functions defined. The first is anonymous (function is not named), and the second is named. When using an arrow expression, we do not use the function declaration. To define an arrow expression you simply use: () => { }. You can pass arguments to an arrow expression between the parenthesis (()).

// Defining an anonymous arrow expression that simply logs a string to the console.

console.log(() => console.log('Shhh, Im anonymous'));

// Defining a named function by creating an arrow expression and saving it to a const variable helloWorld.

const helloWorld = (name) => {

console.log(`Welcome ${name} to Codecademy, this is an arrow expression.`)

};

// Calling the helloWorld() function.

helloWorld('Codey'); //Output: Welcome Codey to Codecademy, this is an Arrow Function Expression.

Promises

A Promise is a JavaScript object that represents the eventual outcome of an asynchronous operation. A Promise has three different outcomes: pending (the result is undefined and the expression is waiting for a result), fulfilled (the promise has been completed successfully and returned a value), and rejected (the promise did not successfully complete, the result is an error object).

In the code below a new Promise is being defined and is passed a function that takes two arguments, a fulfilled condition, and a rejected condition. We then log the returned value of the Promise to the console and chain a .catch() method to handle errors.

// Creating a new Promise and saving it to the testLuck variable. Two arguments are being passed, one for when the promise resolves, and one for if the promise gets rejected.

const testLuck = new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

if (Math.random() < 0.5) {

resolve('Lucky winner!')

} else {

reject(new Error('Unlucky!'))

}

});

testLuck.then(message => {

console.log(message) // Log the resolved value of the Promise

}).catch(error => {

console.error(error) // Log the rejected error of the Promise

});

Resolve and Reject

The Promise constructor method takes a function parameter called the executor function which runs automatically when the constructor is called. The executor function generally starts an asynchronous operation and dictates how the promise should be settled.

The executor function has two function parameters, usually referred to as the resolve() and reject() functions. The resolve() and reject() functions aren’t defined by the programmer. When the Promise constructor runs, JavaScript will pass its own resolve() and reject() functions into the executor function.

- resolve is a function with one argument. Under the hood, if invoked, resolve() will change the promise’s status from pending to fulfilled, and the promise’s resolved value will be set to the argument passed into resolve().

- reject is a function that takes a reason or error as an argument. Under the hood, if invoked, reject() will change the promise’s status from pending to rejected, and the promise’s rejection reason will be set to the argument passed into reject().

Async/Await

The async...await syntax allows developers to easily implement Promise-based code. The keyword async used in conjunction with a function declaration creates an async function that returns a Promise. Async functions allow us to use the keyword await to block the event loop until a given Promise resolves or rejects. The await keyword also allows us to assign the resolved value of a Promise to a variable.

Let’s take a look at the code below. In the code below an asynchronous arrow expression is defined with the async keyword. In the function body we are creating a new Promise which passes a function that is executed after 5 seconds, we await the Promise to resolve and save the value returned to finalResult, and the output of the Promise is logged to the console.

// Creating a new promise that runs the function in the setTimeout after 5 seconds.

const newPromise = new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

setTimeout(() => resolve("All done!"), 5000);

});

// Creating an asynchronous function using an arrow expression and saving it to a the variable asyncFunction.

const asyncFunction = async () => {

// Awaiting the promise to resolve and saving the result to the variable finalResult.

const finalResult = await newPromise;

// Logging the result of the promise to the console

console.log(finalResult); // Output: All done!

}

asyncFunction();

setInterval() and setTimeout()

In addition to utilizing the async...await syntax, we can also use the setInterval() and setTimeout() functions. In the example code of the previous section, we created a setTimeout() instance in the Promise constructor.

The setInterval() function executes a code block at a specified interval, in milliseconds. The setInterval() function requires two arguments: the name of the function (the code block that will be executed), and the number of milliseconds (how often the function will be executed). Optionally, we can pass additional arguments which will be supplied as parameters for the function that will be executed by setInterval(). The setInterval() function will continue to execute until the clearInterval() function is called or the node process is exited. In the code block below, the setInterval() function in the showAlert() function will display an alert box every 5000 milliseconds.

// Defining a function that instantiates setInterval

const showAlert = () => {

// Calling setInterval() and passing a function that shows an alert every 5 seconds.

setInterval(() => {

alert('I show every 5 seconds!')

}, 5000);

};

// Calling the newInterval() function that calls the setInterval

showAlert();

The setTimeout() function executes a code block after a specified amount of time (in milliseconds) and is only executed once. The setTimeout() function accepts the same arguments as the setInterval() function. Using the clearTimeout() function will prevent the function specified from being executed. In the code block below, a function named showTimeout() is declared as an arrow expression. The setTimeout() function is then defined and displays an alert box after 5 seconds.

// Defining a function that calls setTimeout

const showTimeout = () => {

// Calling setTimeout() that passes a function that shows an alert after 5 seconds.

setTimeout(() => {

alert('I only show once after 5 seconds!');

}, 5000);

};

// Calling the showTimeout() function

showTimeout();

Node

The Node REPL (read-eval-print loop)

REPL is an abbreviation for read–eval–print loop. It’s a program that loops, or repeatedly cycles, through three different states: a read state where the program reads input from a user, the eval state where the program evaluates the user’s input, and the print state where the program prints out its evaluation to a console. Then it loops through these states again.

It's just the equivalent of typing python except for javascript. Type node to get to it.

To see global vars see Object.keys(global). You can add to it with global.cat = 'thing'. Print with console.log(global.cat)

If you’re familiar with running JavaScript on the browser, you’ve likely encountered the Window object. Here’s one major way that Node differs: try to access the Window object (this will throw an error). The Window object is the JavaScript object in the browser that holds the DOM, since we don’t have a DOM here, there’s no Window object.

Running a Program with Node

node program

Core Modules

Include a module:

// Require in the 'events' core module:

const events = require('events');

Some core modules are actually used inside other core modules. For instance, the util module can be used in the console module to format messages. We’ll cover these two modules in this lesson, as well as two other commonly used core modules: process and os.

See all builtin modules: require('module').builtinModules

Console Module

Since console is a global module, its methods can be accessed from anywhere, and the require() function is not necessary.

- .log() - prints messages to the terminal

- .assert() - prints a message to the terminal if the value is falsey

console.assert(petsArray.length > 5);- .table() - prints out a table in the terminal from an object or array

The Process Module

Node has a global process object with useful methods and information about the current process. The console.log() method is a "thin wrapper" on the .stdout.write() method of the process object.

The process.env property is an object which stores and controls information about the environment in which the process is currently running. For example, the process.env object contains a PWD property which holds a string with the directory in which the current process is located. It can be useful to have some if/else logic in a program depending on the current environment— a web application in a development phase might perform different tasks than when it’s live to users. We could store this information on the process.env. One convention is to add a property to process.env with the key NODE_ENV and a value of either production or development.

if (process.env.NODE_ENV === 'development'){

console.log('Testing! Testing! Does everything work?');

}

The process.memoryUsage() returns information on the CPU demands of the current process. It returns a property that looks similar to this:

{ rss: 26247168,

heapTotal: 5767168,

heapUsed: 3573032,

external: 8772 }

process.argv holds an array of command line values provided when the current process was initiated.

The OS Module

const os = require('os');

- os.type() — to return the computer’s operating system.

- os.arch() — to return the operating system CPU architecture.

- os.networkInterfaces() — to return information about the network interfaces of the computer, such as IP and MAC address.

- os.homedir() — to return the current user’s home directory.

- os.hostname() — to return the hostname of the operating system.

- os.uptime() — to return the system uptime, in seconds.

Create an empty object const object = {};

Instantiate a dictionary:

const os = require('os');

const server = {type: os.type(), architecture: os.arch(), uptime: os.uptime()};

console.table(server)

The Util Module

Developers sometimes classify outlier functions used to maintain code and debug certain aspects of a program’s functionality as utility functions. Utility functions don’t necessarily create new functionality in a program, but you can think of them as internal tools used to maintain and debug your code. The Node.js util core module contains methods specifically designed for these purposes.

const util = require('util');

Get the type of an object:

const util = require('util');

const today = new Date();

const earthDay = 'April 22, 2022';

console.log(util.types.isDate(today));

console.log(util.types.isDate(earthDay));

Turn callback functions into promises:

Another important util method is .promisify(), which turns callback functions into promises. As you know, asynchronous programming is essential to Node.js. In the beginning, this asynchrony was achieved using error-first callback functions, which are still very prevalent in the Node ecosystem today. But since promises are often preferred over callbacks and especially nested callbacks, Node offers a way to turn these into promises. Let’s take a look:

function getUser (id, callback) {

return setTimeout(() => {

if (id === 5) {

callback(null, { nickname: 'Teddy' })

} else {

callback(new Error('User not found'))

}

}, 1000)

}

function callback (error, user) {

if (error) {

console.error(error.message)

process.exit(1)

}

console.log(`User found! Their nickname is: ${user.nickname}`)

}

getUser(1, callback) // -> `User not found`

getUser(5, callback) // -> `User found! Their nickname is: Teddy`

You can convert the above to:

const getUserPromise = util.promisify(getUser);

getUserPromise(id)

.then((user) => {

console.log(`User found! Their nickname is: ${user.nickname}`);

})

.catch((error) => {

console.log('User not found', error);

});

getUser(1) // -> `User not found`

getUser(5) // -> `User found! Their nickname is: Teddy`

We declare a getUserPromise variable that stores the getUser method turned into a promise using the .promisify() method. With that in place, we’re able to use getUserPromise with .then() and .catch() methods (or we could also use the async...await syntax here) to resolve the promise returned or catch any errors.

NPM

Create a new app

npm init

Add -y to answer yes to everything.

This will generate a package.json file:

{

"name": "my-project",

"version": "1.0.0",

"description": "a basic project",

"main": "index.js",

"scripts": {

"test": "echo \"Error: no test specified\" && exit 1"

},

"author": "Super Coder",

"license": "ISC",

"dependencies": {

"express": "^4.17.1"

},

}

nodemon

Automatically restart a program when a file changes.

npm install nodemon

The npm i <package name> command installs a package locally in a folder called node_modules/ which is created in the project directory that you ran the command from. In addition, the newly installed package will be added to the package.json file.

Package Scope

While most dependencies play a direct role in the functionality of your application, development dependencies are used for the purpose of making development easier or more efficient.

In fact, the nodemon package is actually better suited as a development dependency since it makes developers’ lives easier but makes no changes to the app itself. To install nodemon as a development dependency, we can add the --save-dev flag, or its alias, -D.

npm install nodemon --save-dev

Development dependencies are listed in the "devDependencies" field of the package.json file. This indicates that the package is being used specifically for development and will not be included in a production release of the project.

{

"name": "my-project",

"version": "1.0.0",

"description": "a basic project",

"main": "index.js",

"scripts": {

"test": "echo \"Error: no test specified\" && exit 1"

},

"author": "",

"license": "ISC",

"dependencies": {

"express": "^4.17.1"

},

"devDependencies": {

"nodemon": "^2.0.13"

}

}

Global Packages

Typically, packages installed this way will be used in the command-line rather than imported into a project’s code. One such example is the http-server package which allows you to spin up a zero-configuration server from anywhere in the command-line.

To install a package globally, use the -g flag with the installation command:

npm install http-server -g

http-server is a good package to install globally since it is a general command-line utility and its purpose is not linked to any specific functionality within an app.

Unlike local package dependencies or development dependencies, packages installed globally will not be listed in a projects package.json file and they will be stored in a separate global node_modules/ folder.

Installing a Custom Package

If you want to give someone else your package you can provide the package.json file and then they can install with npm i. Add --production to leave out the dev dependencies.

Modules

There are multiple ways of implementing modules depending on the runtime environment in which your code is executed. In JavaScript, there are two runtime environments and each has a preferred module implementation:

- The Node runtime environment and the module.exports and require() syntax.

- The browser’s runtime environment and the ES6 import/export syntax.

Exporting

/* converters.js */

function celsiusToFahrenheit(celsius) {

return celsius * (9/5) + 32;

}

module.exports.celsiusToFahrenheit = celsiusToFahrenheit;

module.exports.fahrenheitToCelsius = function(fahrenheit) {

return (fahrenheit - 32) * (5/9);

};

- At the top of the new file, converters.js, the function celsiusToFahrenheit() is declared.

- On the next line of code, the first approach for exporting a function from a module is shown. In this case, the already-defined function celsiusToFahrenheit() is assigned to module.exports.celsiusToFahrenheit.

- Below, an alternative approach for exporting a function from a module is shown. In this second case, a new function expression is declared and assigned to module.exports.fahrenheitToCelsius. This new method is designed to convert Fahrenheit values back to Celsius.

- Both approaches successfully store a function within the module.exports object.

module.exports is an object that is built-in to the Node.js runtime environment. Other files can now import this object, and make use of these two functions, with another feature that is built-in to the Node.js runtime environment: the require() function.

Require

The require() function accepts a string as an argument. That string provides the file path to the module you would like to import.

Let’s update water-limits.js such that it uses require() to import the .celsiusToFahrenheit() method from the module.exports object within converters.js:

/* water-limits.js */

const converters = require('./converters.js');

const freezingPointC = 0;

const boilingPointC = 100;

const freezingPointF = converters.celsiusToFahrenheit(freezingPointC);

const boilingPointF = converters.celsiusToFahrenheit(boilingPointC);

console.log(`The freezing point of water in Fahrenheit is ${freezingPointF}`);

console.log(`The boiling point of water in Fahrenheit is ${boilingPointF}`);

Using Object Destructuring to be more Selective With require()

In many cases, modules will export a large number of functions but only one or two of them are needed. You can use object destructuring to extract only the needed functions.

Let’s update celsius-to-fahrenheit.js and only extract the .celsiusToFahrenheit() method, leaving .fahrenheitToCelsius() behind:

/* celsius-to-fahrenheit.js */

const { celsiusToFahrenheit } = require('./converters.js');

const celsiusInput = process.argv[2];

const fahrenheitValue = celsiusToFahrenheit(celsiusInput);

console.log(`${celsiusInput} degrees Celsius = ${fahrenheitValue} degrees Fahrenheit`);

Notice that the first line used to be const converters = require('./converters.js'); and now it is specifying the exported function.

The Events Module

Node provides an EventEmitter class which we can access by requiring in the events core module:

// Require in the 'events' core module

let events = require('events');

// Create an instance of the EventEmitter class

let myEmitter = new events.EventEmitter();

Each event emitter instance has an .on() method which assigns a listener callback function to a named event. The .on() method takes as its first argument the name of the event as a string and, as its second argument, the listener callback function.

Each event emitter instance also has an .emit() method which announces a named event has occurred. The .emit() method takes as its first argument the name of the event as a string and, as its second argument, the data that should be passed

let newUserListener = (data) => {

console.log(`We have a new user: ${data}.`);

};

// Assign the newUserListener function as the listener callback for 'new user' events

myEmitter.on('new user', newUserListener)

// Emit a 'new user' event

myEmitter.emit('new user', 'Lily Pad') //newUserListener will be invoked with 'Lily Pad'

Note There is no link between the variable data in the constructer for the event emitter and the new user name.

User Input and Output

Notice that for user input and output for something like stdin what you're really doing is registering a callback and then calling it on user input. Ex:

process.stdin.on('data', (userInput) => {

let input = userInput.toString()

console.log(input)

});

Notice the on and then here we're just defining an anonymous function.

The Error Module

The Node environment’s error module has all the standard JavaScript errors such as EvalError, SyntaxError, RangeError, ReferenceError, TypeError, and URIError as well as the JavaScript Error class for creating new error instances. Within our own code, we can generate errors and throw them, and, with synchronous code in Node, we can use error handling techniques such as try...catch statements. Note that the error module is within the global scope—there is no need to import the module with the require() statement.

Many asynchronous Node APIs use error-first callback functions—callback functions which have an error as the first expected argument and the data as the second argument. If the asynchronous task results in an error, it will be passed in as the first argument to the callback function. If no error was thrown, the first argument will be undefined.

const errorFirstCallback = (err, data) => {

if (err) {

console.log(`There WAS an error: ${err}`);

} else {

// err was falsy

console.log(`There was NO error. Event data: ${data}`);

}

}

Why Error First Callbacks

You need this because if you try something like:

const api = require('./api.js');

// Not an error-first callback

let callbackFunc = (data) => {

console.log(`Something went right. Data: ${data}\n`);

};

try {

api.naiveErrorProneAsyncFunction('problematic input', callbackFunc);

} catch(err) {

console.log(`Something went wrong. ${err}\n`);

}

then the try-catch won't work because the error is thrown in the context of the separate thread spawned asynchronously and subsequently never caught because Javascript is a garbage programming language.

The Buffer Module

In Node.js, the Buffer module is used to handle binary data. The Buffer module is within the global scope, which means that Buffer objects can be accessed anywhere in the environment without importing the module with require().

A Buffer object represents a fixed amount of memory that can’t be resized. Buffer objects are similar to an array of integers where each element in the array represents a byte of data. The buffer object will have a range of integers from 0 to 255 inclusive.

The Buffer module provides a variety of methods to handle the binary data such as .alloc(), .toString(), .from(), and .concat().

The .alloc() method creates a new Buffer object with the size specified as the first parameter. .alloc() accepts three arguments:

Size: Required. The size of the buffer Fill: Optional. A value to fill the buffer with. Default is 0. Encoding: Optional. Default is UTF-8.

const buffer = Buffer.alloc(5);

console.log(buffer); // Ouput: [0, 0, 0, 0, 0]

The .toString() method translates the Buffer object into a human-readable string. It accepts three optional arguments:

Encoding: Default is UTF-8. Start: The byte offset to begin translating in the Buffer object. Default is 0. End: The byte offset to end translating in the Buffer object. Default is the length of the buffer. The start and end of the buffer are similar to the start and end of an array, where the first element is 0 and increments upwards.

const buffer = Buffer.alloc(5, 'a');

console.log(buffer.toString()); // Output: aaaaa

The .from() method is provided to create a new Buffer object from the specified string, array, or buffer. The method accepts two arguments:

Object: Required. An object to fill the buffer with. Encoding: Optional. Default is UTF-8.

const buffer = Buffer.from('hello');

console.log(buffer); // Output: [104, 101, 108, 108, 111]

The .concat() method joins all buffer objects passed in an array into one Buffer object. .concat() comes in handy because a Buffer object can’t be resized. This method accepts two arguments:

Array: Required. An array containing Buffer objects. Length: Optional. Specifies the length of the concatenated buffer.

const buffer1 = Buffer.from('hello'); // Output: [104, 101, 108, 108, 111]

const buffer2 = Buffer.from('world'); // Output:[119, 111, 114, 108, 100]

const array = [buffer1, buffer2];

const bufferConcat = Buffer.concat(array);

console.log(bufferConcat); // Output: [104, 101, 108, 108, 111, 119, 111, 114, 108, 100]

Readable Streams

const readline = require('readline');

const fs = require('fs');

const myInterface = readline.createInterface({

input: fs.createReadStream('shoppingList.txt')

});

const printData = (data) => {

console.log(`Item: ${data}`);

};

myInterface.on('line', printData);

Further explanation

One of the simplest uses of streams is reading and writing to files line-by-line. To read files line-by-line, we can use the .createInterface() method from the readline core module. .createInterface() returns an EventEmitter set up to emit 'line' events:

const readline = require('readline');

const fs = require('fs');

const myInterface = readline.createInterface({

input: fs.createReadStream('text.txt')

});

myInterface.on('line', (fileLine) => {

console.log(`The line read: ${fileLine}`);

});

Let’s walk through the above code:

- We require in the readline and fs core modules.

- We assign to myInterface the returned value from invoking readline.createInterface() with an object containing our designated input.

- We set our input to fs.createReadStream('text.txt') which will create a stream from the text.txt file.

- Next we assign a listener callback to execute when line events are emitted. A 'line' event will be emitted after each line from the file is read.

- Our listener callback will log to the console 'The line read: [fileLine]', where [fileLine] is the line just read.

Writable Streams

const readline = require('readline');

const fs = require('fs');

const myInterface = readline.createInterface({

input: fs.createReadStream('shoppingList.txt')

});

const fileStream = fs.createWriteStream('shoppingResults.txt');

let transformData = (line) => {

fileStream.write(`They were out of: ${line}\n`);

};

myInterface.on('line', transformData);

Timers Modules

You may already be familiar with some timer functions such as, setTimeout() and setInterval(). Timer functions in Node.js behave similarly to how they work in front-end JavaScript programs, but the difference is that they are added to the Node.js event loop. This means that the timer functions are scheduled and put into a queue. This queue is processed at every iteration of the event loop. If a timer function is executed outside of a module, the behavior will be random (non-deterministic).

The setImmediate() function is often compared with the setTimeout() function. When setImmediate() is called, it executes the specified callback function after the current (poll phase) is completed. The method accepts two parameters: the callback function (required) and arguments for the callback function (optional). If you instantiate multiple setImmediate() functions, they will be queued for execution in the order that they were created.

HTTP Server

To process HTTP requests in JavaScript and Node.js, we can use the built-in http module. This core module is key in leveraging Node.js networking and is extremely useful in creating HTTP servers and processing HTTP requests.

The http module comes with various methods that are useful when engaging with HTTP network requests. One of the most commonly used methods within the http module is the .createServer() method. This method is responsible for doing exactly what its namesake implies; it creates an HTTP server. To implement this method to create a server, the following code can be used:

const server = http.createServer((req, res) => {

res.end('Server is running!');

});

server.listen(8080, () => {

const { address, port } = server.address();

console.log(`Server is listening on: http://${address}:${port}`);

})

The .createServer() method takes a single argument in the form of a callback function. This callback function has two primary arguments; the request (commonly written as req) and the response (commonly written as res).

The req object contains all of the information about an HTTP request ingested by the server. It exposes information such as the HTTP method (GET, POST, etc.), the pathname, headers, body, and so on. The res object contains methods and properties pertaining to the generation of a response by the HTTP server. This object contains methods such as .setHeader() (sets HTTP headers on the response), .statusCode (set the status code of the response), and .end() (dispatches the response to the client who made the request). In the example above, we use the .end() method to send the string ‘Server is Running!’ to the client, which will display on the web page.

Once the .createServer() method has instantiated the server, it must begin listening for connections. This final step is accomplished by the .listen() method on the server instance. This method takes a port number as the first argument, which tells the server to listen for connections at the given port number. In our example above, the server has been set to listen on port 8080. Additionally, the .listen() method takes an optional callback function as a second argument, allowing it to carry out a task after the server has successfully started.

Using this simple .createServer() method, in conjunction with the callback, provides the ability to process HTTP requests dynamically and dispatch responses back to their callers.

The URL Module

Typically, an HTTP server will require information from the request URL to accurately process a request. This request URL is located on the url property contained within the req object itself. To parse the different parts of this URL easily, Node.js provides the built-in url module. The core of the url module revolves around the URL class. A new URL object can be instantiated using the URL class as follows:

const url = new URL('https://www.example.com/p/a/t/h?query=string');

Once instantiated, different parts of the URL can be accessed and modified via various properties, which include:

- hostname: Gets and sets the host name portion of the URL.

- pathname: Gets and sets the path portion of the URL.

- searchParams: Gets the search parameter object representing the query parameters contained within the URL. Returns an instance of the URLSearchParams class.

You might recognize the URL and URLSearchParams classes if you are familiar with browser-based JavaScript. It’s because they are actually the same thing! These classes are defined by the WHATWG URL specification. Both the browser and Node.js implement this API, which means developers can have a similar developer experience working with both client and server-side JavaScript.

Using these properties, one can break the URL down into easily usable parts for processing the request.

const host = url.hostname; // example.com

const pathname = url.pathname; // /p/a/t/h

const searchParams = url.searchParams; // {query: 'string'}

While the url module can be used to deconstruct a URL into its constituent parts, it can also be used to construct a URL. Constructing a URL via this method relies on most of the same properties listed above to set values on the URL instead of retrieving them. This can be done by setting each of these values equal to a value for the newly constructed URL. Once all parts of the URL have been added, the composed URL can be obtained using the .toString() method.

const createdUrl = new URL('https://www.example.com');

createdUrl.pathname = '/p/a/t/h';

createdUrl.search = '?query=string';

createUrl.toString(); // Creates https://www.example.com/p/a/t/h?query=string

Routing

To process and respond to requests appropriately, servers need to do more than look at a request and dispatch a response. Internally, a server needs to maintain a way to handle each request based on specific criteria such as method, pathname, etc. The process of handling requests in specific ways based on the information provided within the request is known as routing.

The method is one important piece of information that can be used to route requests. Since each HTTP request contains a method such as GET and POST, it is a great way to discern different classes of requests based on the action intended for the server to carry out. Thus, all GET requests could be routed to a specific function for handling, while all POST requests are routed to another function to be handled. This also allows for the logical co-location of processing code with the specific verb to be handled.

const server = http.createServer((req, res) => {

const { method } = req;

switch(method) {

case 'GET':

return handleGetRequest(req, res);

case 'POST':

return handlePostRequest(req, res);

case 'DELETE':

return handleDeleteRequest(req, res);

case 'PUT':

return handlePutRequest(req, res);

default:

throw new Error(`Unsupported request method: ${method}`);

}

})

In the above example, the HTTP method property is destructured from the req object and used to conditionally invoke a handler function built specifically for handling those types of requests. This is great at first glance, but it should soon become apparent that the routing is not specific enough. After all, how will one GET request be distinguished from another?

We can distinguish one request from another of the same method through the use of the pathname. The pathname allows the server to understand what resource is being targeted. Let’s take a look at the handleGetRequest handler function.

function handleGetRequest(req, res) {

const { pathname } = new URL(req.url);

let data = {};

if (pathname === '/projects') {

data = await getProjects();

res.setHeader('Content-Type', 'application/json');

return res.end(JSON.stringify(data));

}

res.statusCode = 404;

return res.end('Requested resource does not exist');

}

Within the handleGetRequest() function, the pathname is being checked to match a known resource, '/projects'. If the pathname matches, the resource data is fetched and then subsequently dispatched from the server as a successful response. Otherwise, the .statusCode property is set to 404, indicating that the resource is not found, and a corresponding error message is dispatched. This pattern can be extrapolated to any number of conditional resource matches, allowing the server to handle many different types of requests to different resources.

Longer Example

const http = require('http');

// Handle get request

const handleGetRequest = (req, res) => {

const pathname = req.url;

if (pathname === '/users') {

res.end(JSON.stringify([]));

}

}

// Creates server instance

const server = http.createServer((req, res) => {

const { method } = req;

switch(method) {

case 'GET':

return handleGetRequest(req, res);

default:

throw new Error(`Unsupported request method: ${method}`);

}

});

// Starts server listening on specified port

server.listen(4001, () => {

const { address, port } = server.address();

console.log(`Server is listening on: http://${address}:${port}`);

});

Returning a Status Code

const http = require('http');

const handleGetRequest = (req, res) => {

res.statusCode = 200;

return res.end(JSON.stringify({ data: [] }));

}

const handlePostRequest = (req, res) => {

res.statusCode = 500;

return res.end("Unable to create record");

}

// Creates server instance

const server = http.createServer((req, res) => {

const { method } = req;

switch(method) {

case 'GET':

return handleGetRequest(req, res);

case 'POST':

return handlePostRequest(req, res);

default:

throw new Error(`Unsupported request method: ${method}`);

}

});

// Starts server listening on specified port

server.listen(4001, () => {

const { address, port } = server.address();

console.log(`Server is listening on: http://${address}:${port}`);

});

Express

Request Object Properties

| Index | Properties | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | req.app | This is used to hold a reference to the instance of the express application that is using the middleware. |

| 2. | req.baseurl | It specifies the URL path on which a router instance was mounted. |

| 3. | req.body | It contains key-value pairs of data submitted in the request body. By default, it is undefined, and is populated when you use body-parsing middleware such as body-parser. |

| 4. | req.cookies | When we use cookie-parser middleware, this property is an object that contains cookies sent by the request. |

| 5. | req.fresh | It specifies that the request is "fresh." it is the opposite of req.stale. |

| 6. | req.hostname | It contains the hostname from the "host" http header. |

| 7. | req.ip | It specifies the remote IP address of the request. |

| 8. | req.ips | When the trust proxy setting is true, this property contains an array of IP addresses specified in the ?x-forwarded-for? request header. |

| 9. | req.originalurl | This property is much like req.url; however, it retains the original request URL, allowing you to rewrite req.url freely for internal routing purposes. |

| 10. | req.params | An object containing properties mapped to the named route ?parameters?. For example, if you have the route /user/:name, then the "name" property is available as req.params.name. This object defaults to {}. |

| 11. | req.path | It contains the path part of the request URL. |

| 12. | req.protocol | The request protocol string, "http" or "https" when requested with TLS. |

| 13. | req.query | An object containing a property for each query string parameter in the route. |

| 14. | req.route | The currently-matched route, a string. |

| 15. | req.secure | A Boolean that is true if a TLS connection is established. |

| 16. | req.signedcookies | When using cookie-parser middleware, this property contains signed cookies sent by the request, unsigned and ready for use. |

| 17. | req.stale | It indicates whether the request is "stale," and is the opposite of req.fresh. |

| 18. | req.subdomains | It represents an array of subdomains in the domain name of the request. |

| 19. | req.xhr | A Boolean value that is true if the request's "x-requested-with" header field is "xmlhttprequest", indicating that the request was issued by a client library such as jQuery |

Request Object Methods

req.accepts

This method is used to check whether the specified content types are acceptable, based on the request's Accept HTTP header field.

req.accepts('html');

//=>?html?

req.accepts('text/html');

// => ?text/html?

req.get(field)

This method returns the specified HTTP request header field.

req.get('Content-Type');

// => "text/plain"

req.get('content-type');

// => "text/plain"

req.get('Something');

// => undefined

req.is(type)

// With Content-Type: text/html; charset=utf-8

req.is('html');

req.is('text/html');

req.is('text/*');

// => true

req.param(name [,defaultValue])

This method is used to fetch the value of param name when present.

// ?name=sasha

req.param('name')

// => "sasha"

// POST name=sasha

req.param('name')

// => "sasha"

// /user/sasha for /user/:name

req.param('name')

// => "sasha"

Response Object

Knex.js

How does exports.up and exports.down work

http://perkframework.com/v1/guides/database-migrations-knex.html

Seed Files

A seed file allows you to add data into your database without having to manually add it. This is most frequently used for database initialization or loading demo data.

Babel

What is Babel: https://babeljs.io/docs/en/

ReactJS

Importing React Required Code

import React from 'react';

This creates an object named React which contains methods necessary to use the React library.

import ReactDOM from 'react-dom';

The methods imported from 'react-dom' are meant for interacting with the DOM. You are already familiar with one of them: ReactDOM.render().

The methods imported from 'react' don’t deal with the DOM at all. They don’t engage directly with anything that isn’t part of React.

To clarify: the DOM is used in React applications, but it isn’t part of React. After all, the DOM is also used in countless non-React applications. Methods imported from 'react' are only for pure React purposes, such as creating components or writing JSX elements.

Components

Create a Component Class

we can use a JavaScript class to define a new React component. We can also define components with JavaScript functions, but we’ll focus on class components first.

All class components will have some methods and properties in common (more on this later). Rather than rewriting those same properties over and over again every time, we extend the Component class from the React library. This way, we can use code that we import from the React library, without having to write it over and over again ourselves.

After we define our class component, we can use it to render as many instances of that component as we want.

What is React.Component, and how do you use it to make a component class?

React.Component is a JavaScript class. To create your own component class, you must subclass React.Component. You can do this by using the syntax class YourComponentNameGoesHere extends React.Component {}.

import React from 'react';

import ReactDOM from 'react-dom';

class MyComponentClass extends React.Component {

render() {

return <h1>Hello world</h1>;

}

}

ReactDOM.render(

<MyComponentClass />,

document.getElementById('app')

);

On line 4, you know that you are declaring a new component class, which is like a factory for building React components. You know that React.Component is a class, which you must subclass in order to create a component class of your own. You also know that React.Component is a property on the object which was returned by import React from 'react' on line 1.

The Render Function

A render method is a property whose name is render, and whose value is a function. The term "render method" can refer to the entire property, or to just the function part.

class ComponentFactory extends React.Component {

render() {

return <h1>Hello world</h1>;

}

}

Create a Component Instance

To make a React component, you write a JSX element. Instead of naming your JSX element something like h1 or div like you’ve done before, give it the same name as a component class. Voilà, there’s your component instance! JSX elements can be either HTML-like, or component instances. JSX uses capitalization to distinguish between the two! That is the React-specific reason why component class names must begin with capital letters. In a JSX element, that capitalized first letter says, "I will be a component instance and not an HTML tag."

Whenever you make a component, that component inherits all of the methods of its component class. MyComponentClass has one method: MyComponentClass.render(). Therefore,

In order to render a component, that component needs to have a method named render. Your component has this! It inherited a method named render from MyComponentClass.

To call a component’s render method, you pass that component to ReactDOM.render(). Notice your component, being passed as ReactDOM.render()‘s first argument:

ReactDOM.render(

<MyComponentClass />,

document.getElementById('app')

);

ReactDOM.render() will tell

Hello world

. ReactDOM.render() will then take that resulting JSX element, and add it to the virtual DOM. This will make "Hello world" appear on the screen.Use This in a Class

class IceCreamGuy extends React.Component {

get food() {

return 'ice cream';

}

render() {

return <h1>I like {this.food}.</h1>;

}

}

Render Components with Components

class OMG extends React.Component {

render() {

return <h1>Whooaa!</h1>;

}

}

class Crazy extends React.Component {

render() {

return <OMG />;

}

}

Importing Files and Exporting Functionality

Importing

The second important difference involves the contents of the string at the end of the statement: 'react' vs './NavBar.js'.

If you use an import statement, and the string at the end begins with either a dot or a slash, then import will treat that string as a filepath. import will follow that filepath, and import the file that it finds.

If your filepath doesn’t have a file extension, then ".js" is assumed. So the above example could be shortened:

import { NavBar } from './NavBar';

One final, important note: None of this behavior is specific to React! Module systems of independent, importable files are a very popular way to organize code. React’s specific module system comes from ES6.

Exporting

This is called a named export.

export class NavBar extends React.Component {

Component Props

A component’s props is an object. It holds information about that component. You can pass information to a prop via an attribute.

import React from 'react';

import ReactDOM from 'react-dom';

class Greeting extends React.Component {

render() {

return <h1>Hi there, {this.props.firstName}!</h1>;

}

}

ReactDOM.render(

<Greeting firstName='Grant' />,

document.getElementById('app')

);

Event Handler

import React from 'react';

import ReactDOM from 'react-dom';

import { Button } from './Button';

class Talker extends React.Component {

talk() {

let speech = '';

for (let i = 0; i < 10000; i++) {

speech += 'blah ';

}

alert(speech);

}

render() {

return <Button talk={this.talk}/>;

ReactDOM.render(

<Talker />,

document.getElementById('app')

);

// ****************************************

// In Button.js

import React from 'react';

export class Button extends React.Component {

render() {

return (

// TODO - why is it `this` here?

<button onClick={this.props.talk}>

Click me!

</button>

);

}

}

handleEvent, onEvent, and this.props.onEvent

When you pass an event handler as a prop, as you just did, there are two names that you have to choose.

Both naming choices occur in the parent component class - that is, in the component class that defines the event handler and passes it.

The first name that you have to choose is the name of the event handler itself.

Look at Talker.js, lines 6 through 12. This is our event handler. We chose to name it talk.

The second name that you have to choose is the name of the prop that you will use to pass the event handler. This is the same thing as your attribute name.

For our prop name, we also chose talk, as shown on line 15:

return <Button talk={this.talk} />;

These two names can be whatever you want. However, there is a naming convention that they often follow. You don’t have to follow this convention, but you should understand it when you see it.

Here’s how the naming convention works: first, think about what type of event you are listening for. In our example, the event type was "click."

If you are listening for a "click" event, then you name your event handler handleClick. If you are listening for a "keyPress" event, then you name your event handler handleKeyPress:

class MyClass extends React.Component {

handleHover() {

alert('I am an event handler.');

alert('I will be called in response to "hover" events.');

}

}

Your prop name should be the word on, plus your event type. If you are listening for a "click" event, then you name your prop onClick. If you are listening for a "keyPress" event, then you name your prop onKeyPress:

class MyClass extends React.Component {

handleHover() {

alert('I am an event handler.');

alert('I will listen for a "hover" event.');

}

render() {

return <Child onHover={this.handleHover} />;

}

}

this.props.children

Every component’s props object has a property named children.

this.props.children will return everything in between a component’s opening and closing JSX tags. For example:

// List.js

import React from 'react';

export class List extends React.Component {

render() {

let titleText = `Favorite ${this.props.type}`;

if (this.props.children instanceof Array) {

// Add an s to make it plural if there is more than one

titleText += 's';

}

return (

<div>

<h1>{titleText}</h1>

<ul>{this.props.children}</ul>

</div>

);

}

}

// App.js

import React from 'react';

import ReactDOM from 'react-dom';

import { List } from './List';

class App extends React.Component {

render() {

return (

<div>

<List type='Living Musician'>

<li>Sachiko M</li>

<li>Harvey Sid Fisher</li>

</List>

<List type='Living Cat Musician'>

<li>Nora the Piano Cat</li>

</List>

</div>

);

}

}

ReactDOM.render(

<App />,

document.getElementById('app')

);

This will print:

Favorite Living Musicians

Sachiko M

Harvey Sid Fisher

Favorite Living Cat Musician

Nora the Piano Cat

Because in List.js, between the <ul></ul> you have {this.props.children} which grabs all the elements between <List></List> in the App class.

Default Properties

Used if nothing is passed into the property.

import React from 'react';

import ReactDOM from 'react-dom';

class Button extends React.Component {

render() {

return (

<button>

{this.props.text}

</button>

);

}

}

// defaultProps goes here:

Button.defaultProps = {text: "I am a button"};

ReactDOM.render(

<Button />,

document.getElementById('app')

);

Component State

A React component can access dynamic information in two ways: props and state.

Unlike props, a component’s state is not passed in from the outside. A component decides its own state.

To make a component have state, give the component a state property. This property should be declared inside of a constructor method, like this:

class Example extends React.Component {

constructor(props) {

super(props);

this.state = { mood: 'decent' };

}

render() {

return <div></div>;

}

}

<Example />

// Access the state outside with this.state.mood

// You can set the state with this.setState({mood: "the mood"})

What is super(props) Also: https://overreacted.io/why-do-we-write-super-props/

this.setState from Another Function

You'll use a wrapper function to call this.setState from another function. Like this:

class Example extends React.Component {

constructor(props) {

super(props);

this.state = { weather: 'sunny' };

this.makeSomeFog = this.makeSomeFog.bind(this);

}

makeSomeFog() {

this.setState({

weather: 'foggy'

});

}

}

The line this.makeSomeFog = this.makeSomeFog.bind(this); is necessary because makeSomeFog()'s body contains the word this. It has to do with the way event handlers are bound in Javascript. If you use this without the line this.makeSomeFog = this.makeSomeFog.bind(this); with an event handler the this word will be lost so we have to bind it... because Javascript. If the function isn't used by an event handler then it won't matter.

Full example

import React from 'react';

import ReactDOM from 'react-dom';

const green = '#39D1B4';

const yellow = '#FFD712';

class Toggle extends React.Component {

constructor(props) {

super(props);

this.state = {color: green};

this.changeColor = this.changeColor.bind(this);

}

changeColor() {

if(this.state.color === yellow) {

this.setState({color: green});

} else {

this.setState({color: yellow});

}

}

render() {

return (

<div style={{background: this.state.color}}>

<h1>

<button onClick={this.changeColor}>

Change color

</button>

</h1>

</div>

);

}

}

ReactDOM.render(<Toggle />, document.getElementById('app'));

NOTE: Anytime you call this.setState it automatically calls render as soon as the state has changed. This is why you don't have to call render again.

Component Lifecycle

We’ve seen that React components can be highly dynamic. They get created, rendered, added to the DOM, updated, and removed. All of these steps are part of a component’s lifecycle.

The component lifecycle has three high-level parts:

- Mounting, when the component is being initialized and put into the DOM for the first time

- Updating, when the component updates as a result of changed state or changed props

- Unmounting, when the component is being removed from the DOM Every React component you’ve ever interacted with does the first step at a minimum. If a component never mounted, you’d never see it!

Most interesting components are updated at some point. A purely static component—like, for example, a logo—might not ever update. But if a component’s state changes, it updates. Or if different props are passed to a component, it updates.

Finally, a component is unmounted when it’s removed from the DOM. For example, if you have a button that hides a component, chances are that component will be unmounted. If your app has multiple screens, it’s likely that each screen (and all of its child components) will be unmounted. If a component is "alive" for the entire lifetime of your app (say, a top-level

It’s worth noting that each component instance has its own lifecycle. For example, if you have 3 buttons on a page, then there are 3 component instances, each with its own lifecycle. However, once a component instance is unmounted, that’s it—it will never be re-mounted, or updated again, or unmounted.

React components have several methods, called lifecycle methods, that are called at different parts of a component’s lifecycle. This is how you, the programmer, deal with the lifecycle of a component.

You may not have known it, but you’ve already used two of the most common lifecycle methods: constructor() and render()! constructor() is the first method called during the mounting phase. render() is called later during the mounting phase, to render the component for the first time, and during the updating phase, to re-render the component.

Notice that lifecycle methods don’t necessarily correspond one-to-one with part of the lifecycle. constructor() only executes during the mounting phase, but render() executes during both the mounting and updating phase.

componentDidMount

Say you want a component to update itself at a setInterval. You don't want to put it in the constructor because that would violate the single responsibility rule but you also don't want it in render because then it would be called on update AND on mounting. That's what componentDidMount is for.

componentDidMount() is the final method called during the mounting phase. The order is:

- The constructor

- render()

- componentDidMount()

In other words, it’s called after the component is rendered.

(Another method, getDerivedStateFromProps(), is called between the constructor and render(), but it is very rarely used and usually isn’t the best way to achieve your goals. We won’t be talking about it in this lesson.)

import React from 'react';

import ReactDOM from 'react-dom';

class Clock extends React.Component {

constructor(props) {

super(props);

this.state = { date: new Date() };

}

render() {

return <div>{this.state.date.toLocaleTimeString()}</div>;

}

componentDidMount() {

const oneSecond = 1000;

setInterval(() => {

this.setState({ date: new Date() });

}, oneSecond);

}

}

ReactDOM.render(<Clock />, document.getElementById('app'));

componentWillUnmount

In the case of our interval above, the problem is now that timer will never stop. If we want to remove it. We want to use clearInterval() to clean it up. We can call this during componentWillUnmount

import React from 'react';

export class Clock extends React.Component {

constructor(props) {

super(props);

this.state = { date: new Date() };

}

render() {

return <div>{this.state.date.toLocaleTimeString()}</div>;

}

componentDidMount() {

const oneSecond = 1000;

this.intervalID = setInterval(() => {

this.setState({ date: new Date() });

}, oneSecond);

}

componentWillUnmount() {

clearInterval(this.intervalID);

}

}

componentDidUpdate

When a component updates many things happen but there are two primary methods - render and componentDidUpdate.

import React from 'react';

export class Clock extends React.Component {

constructor(props) {

super(props);

this.state = { date: new Date() };

}

render() {

return (

<div>

{this.props.isPrecise

? this.state.date.toISOString()

: this.state.date.toLocaleTimeString()}

</div>

);

}

startInterval() {

let delay;

if (this.props.isPrecise) {

delay = 100;

} else {

delay = 1000;

}

this.intervalID = setInterval(() => {

this.setState({ date: new Date() });

}, delay);

}

componentDidMount() {

this.startInterval();

}

componentDidUpdate(prevProps) {

if (this.props.isPrecise === prevProps.isPrecise) {

return;

}

clearInterval(this.intervalID);

this.startInterval();

}

componentWillUnmount() {

clearInterval(this.intervalID);

}

}

Stateless Functional Components

We used to use classes for components but now we use functions.

// Original class-based way of writing components

import React from 'react';

import ReactDOM from 'react-dom';

export class Friend extends React.Component {

render() {

return <img src="https://content.codecademy.com/courses/React/react_photo-octopus.jpg" />;

}

};

ReactDOM.render(

<Friend />,

document.getElementById('app')

);

// Function Version

import React from 'react';

import ReactDOM from 'react-dom';

export const Friend = () => {

return <img src="https://content.codecademy.com/courses/React/react_photo-octopus.jpg" />;

}

ReactDOM.render(

<Friend />,

document.getElementById('app')

);

Function Component Props

export function YesNoQuestion (props) {

return (

<div>

<p>{props.prompt}</p>

<input value="Yes" />

<input value="No" />

</div>

);

}

ReactDOM.render(

<YesNoQuestion prompt="Have you eaten an apple today?" />,

document.getElementById('app');

);

React Hooks

With Hooks, we can use simple function components to do lots of the fancy things that we could only do with class components in the past.

React Hooks, plainly put, are functions that let us manage the internal state of components and handle post-rendering side effects directly from our function components. Hooks don’t work inside classes — they let us use fancy React features without classes. Keep in mind that function components and React Hooks do not replace class components. They are completely optional; just a new tool that we can take advantage of.

Note: If you’re familiar with lifecycle methods of class components, you could say that Hooks let us "hook into" state and lifecycle features directly from our function components.

React offers a number of built-in Hooks. A few of these include useState(), useEffect(), useContext(), useReducer(), and useRef(). See the full list in the docs.

- With React, we feed static and dynamic data models to JSX to render a view to the screen

- Use Hooks to “hook into” internal component state for managing dynamic data in function components

- We employ the State Hook by using the code below:

- currentState to reference the current value of state

- stateSetter to reference a function used to update the value of this state

- the initialState argument to initialize the value of state for the component’s first render

const [currentState, stateSetter] = useState( initialState ); - Call state setters in event handlers

- Define simple event handlers inline with our JSX event listeners and define complex event handlers outside of our JSX

- Use a state setter callback function when our next value depends on our previous value

- Use arrays and objects to organize and manage related data that tends to change together

- Use the spread syntax on collections of dynamic data to copy the previous state into the next state like so: setArrayState((prev) => [ ...prev ]) and setObjectState((prev) => ({ ...prev }))

- Split state into multiple, simpler variables instead of throwing it all into one state object

Comparison Class vs Function

Class

import React, { Component } from "react";

import NewTask from "../Presentational/NewTask";

import TasksList from "../Presentational/TasksList";

export default class AppClass extends Component {

constructor(props) {

super(props);

this.state = {

newTask: {},

allTasks: []

};

this.handleChange = this.handleChange.bind(this);

this.handleSubmit = this.handleSubmit.bind(this);

this.handleDelete = this.handleDelete.bind(this);

}

handleChange({ target }){

const { name, value } = target;

this.setState((prevState) => ({

...prevState,

newTask: {

...prevState.newTask,

[name]: value,

id: Date.now()

}

}));

}

handleSubmit(event){

event.preventDefault();

if (!this.state.newTask.title) return;

this.setState((prevState) => ({

allTasks: [prevState.newTask, ...prevState.allTasks],

newTask: {}

}));

}

handleDelete(taskIdToRemove){

this.setState((prevState) => ({

...prevState,

allTasks: prevState.allTasks.filter((task) => task.id !== taskIdToRemove)

}));

}

render() {

return (

<main>

<h1>Tasks</h1>

<NewTask

newTask={this.state.newTask}

handleChange={this.handleChange}

handleSubmit={this.handleSubmit}

/>

<TasksList

allTasks={this.state.allTasks}

handleDelete={this.handleDelete}

/>

</main>

);

}

}

Function

import React, { useState } from "react";

import NewTask from "../Presentational/NewTask";

import TasksList from "../Presentational/TasksList";

export default function AppFunction() {

const [newTask, setNewTask] = useState({});

const handleChange = ({ target }) => {

const { name, value } = target;

setNewTask((prev) => ({ ...prev, id: Date.now(), [name]: value }));

};

const [allTasks, setAllTasks] = useState([]);

const handleSubmit = (event) => {

event.preventDefault();

if (!newTask.title) return;

setAllTasks((prev) => [newTask, ...prev]);

setNewTask({});

};

const handleDelete = (taskIdToRemove) => {

setAllTasks((prev) => prev.filter(

(task) => task.id !== taskIdToRemove

));

};

return (

<main>

<h1>Tasks</h1>

<NewTask

newTask={newTask}

handleChange={handleChange}

handleSubmit={handleSubmit}

/>

<TasksList allTasks={allTasks} handleDelete={handleDelete} />

</main>

);

}

Update Function Component State

Let’s get started with the State Hook, the most common Hook used for building React components. The State Hook is a named export from the React library, so we import it like this:

import React, { useState } from 'react';

useState() is a JavaScript function defined in the React library. When we call this function, it returns an array with two values:

- current state - the current value of this state

- state setter - a function that we can use to update the value of this state

Because React returns these two values in an array, we can assign them to local variables, naming them whatever we like. For example:

const [toggle, setToggle] = useState();

import React, { useState } from "react";

function Toggle() {

const [toggle, setToggle] = useState();

return (

<div>

<p>The toggle is {toggle}</p>

<button onClick={() => setToggle("On")}>On</button>

<button onClick={() => setToggle("Off")}>Off</button>

</div>

);

}

Notice how the state setter function, setToggle(), is called by our onClick event listeners. To update the value of toggle and re-render this component with the new value, all we need to do is call the setToggle() function with the next state value as an argument.

No need to worry about binding functions to class instances, working with constructors, or dealing with the this keyword. With the State Hook, updating state is as simple as calling a state setter function.

Calling the state setter signals to React that the component needs to re-render, so the whole function defining the component is called again. The magic of useState() is that it allows React to keep track of the current value of state from one render to the next!

More complex example:

import React, { useState } from 'react';

export default function ColorPicker() {

const [color, setColor] = useState();

const divStyle = {backgroundColor: color};

return (

<div style={divStyle}>

<p>The color is {color}</p>

<button onClick={() => setColor('Aquamarine')}>

Aquamarine

</button>

<button onClick={() => setColor('BlueViolet')}>

BlueViolet

</button>

<button onClick={() => setColor('Chartreuse')}>

Chartreuse

</button>

<button onClick={() => setColor('CornflowerBlue')}>

CornflowerBlue

</button>

</div>

);

}

Initialize State

You can set a state at the beginning with: const [color, setColor] = useState("Tomato");.

There are three ways in which this code affects our component:

- During the first render, the initial state argument is used.

- When the state setter is called, React ignores the initial state argument and uses the new value.

- When the component re-renders for any other reason, React continues to use the same value from the previous render.

Use State Setter Outside of JSX

https://www.codecademy.com/courses/react-101/lessons/the-state-hook/exercises/use-state-setter-outside-of-jsx

Let’s see how to manage the changing value of a string as a user types into a text input field:

import React, { useState } from 'react';

export default function EmailTextInput() {

const [email, setEmail] = useState('');

const handleChange = (event) => {

const updatedEmail = event.target.value;

setEmail(updatedEmail);

}

return (

// Here value={email} will set the value to the current

// value in e-mail in the event hook

<input value={email} onChange={handleChange} />

);

}

Let’s break down how this code works!

- The square brackets on the left side of the assignment operator signal array destructuring

- The local variable named email is assigned the current state value at index 0 from the array returned by useState()

- The local variable named setEmail() is assigned a reference to the state setter function at index 1 from the array returned by useState()

- It’s convention to name this variable using the current state variable (email) with "set" prepended

The JSX input tag has an event listener called onChange. This event listener calls an event handler each time the user types something in this element. In the example above, our event handler is defined inside of the definition for our function component, but outside of our JSX. Earlier in this lesson, we wrote our event handlers right in our JSX. Those inline event handlers work perfectly fine, but when we want to do something more interesting than just calling the state setter with a static value, it’s a good idea to separate that logic from everything else going on in our JSX. This separation of concerns makes our code easier to read, test, and modify.

You can change:

const updatedEmail = event.target.value;

setEmail(updatedEmail);

// to this

const handleChange = ({target}) => setEmail(target.value);

Longer Example

import React, { useState } from "react";

// regex to match numbers between 1 and 10 digits long

const validPhoneNumber = /^\d{1,10}$/;

export default function PhoneNumber() {

const [phone, setPhone] = useState('');

const handleChange = ({ target })=> {

const newPhone = target.value;

const isValid = validPhoneNumber.test(newPhone);

if (isValid) {

setPhone(newPhone);

}

// just ignore the event, when new value is invalid

};

return (

<div className='phone'>

<label for='phone-input'>Phone: </label>

<input value={phone} onChange={handleChange} id='phone-input' />

</div>

);

}

Set From Previous State

Often, the next value of our state is calculated using the current state. In this case, it is best practice to update state with a callback function. If we do not, we risk capturing outdated, or “stale”, state values.

import React, { useState } from 'react';

export default function Counter() {

const [count, setCount] = useState(0);

const increment = () => setCount(prevCount => prevCount + 1);

return (

<div>

<p>Wow, you've clicked that button: {count} times</p>

<button onClick={increment}>Click here!</button>

</div>

);

}

When the button is pressed, the increment() event handler is called. Inside of this function, we use our setCount() state setter in a new way! Because the next value of count depends on the previous value of count, we pass a callback function as the argument for setCount() instead of a value (as we’ve done in previous exercises).

setCount(prevCount => prevCount + 1)

When our state setter calls the callback function, this state setter callback function takes our previous count as an argument. The value returned by this state setter callback function is used as the next value of count (in this case prevCount + 1). Note: We can just call setCount(count +1) and it would work the same in this example… but for reasons that are out of scope for this lesson, it is safer to use the callback method.

Arrays in State

import React, { useState } from "react";

import ItemList from "./ItemList";

import { produce, pantryItems } from "./storeItems";

export default function GroceryCart() {

// declare and initialize state

const [cart, setCart] = useState([]);

// addItem is the event handler and will receive the item that

// gets clicked

const addItem = (item) => {

// setCart is the state setter

// and it will tell the component to update its state.

// Via the magic that is the totality of Javascript, it

// will magically receive the previous state to this function

// We then use spread syntax to expand the previous array

// and add it with the item.

setCart((prev) => {

return [item, ...prev];

});

};

// This removes the item at some set index.

const removeItem = (targetIndex) => {

setCart((prev) => {

return prev.filter((item, index) => index !== targetIndex);

});

};

return (

<div>

<h1>Grocery Cart</h1>

<ul>

{cart.map((item, index) => (

<li onClick={() => removeItem(index)} key={index}>

{item}

</li>

))}

</ul>

<h2>Produce</h2>

<ItemList items={produce} onItemClick={addItem} />

<h2>Pantry Items</h2>

<ItemList items={pantryItems} onItemClick={addItem} />

</div>

);

}

Objects in State

export default function Login() {

const [formState, setFormState] = useState({});

const handleChange = ({ target }) => {

const { name, value } = target;

setFormState((prev) => ({

...prev,

[name]: value

}));

};

return (

<form>

<input

value={formState.firstName}

onChange={handleChange}

name="firstName"

type="text"

/>

<input

value={formState.password}

onChange={handleChange}

type="password"

name="password"

/>

</form>

);

}

A few things to notice: